Note: This post originally appeared in issue #31 of my newsletter, Stillnotes. Subscribe there for my newest images and essays.

The impetus

Last fall I experimented with video for an ill-advised weeknight adventure I went on with my friend Nate. Our goal? To do the Arapahoe traverse, a third class ridge scramble in the mountains west of Boulder, all after work on a Tuesday. I borrowed his GoPro with the thought of putting together a video from the experience. The adventure itself was heinous in all the ways it should’ve been—moose run-ins during the rut, getting snowed on above treeline, not even making it to the traverse, and scampering six miles back down in the dark. But I didn’t come away from the evening having learned the value of better planning, no I’m sure I’ll make that mistake again many times. What I discovered is a gap in my photography approach, which I realized while looking through the video files afterwards.

A concept that wasn’t new to me is the idea of three types of shots: wide, medium, tight. Each has their own purpose and each is needed to tell a balanced story. Looking through my video clips, I realized I only had wide shots, broad landscape scenes showing where we were. All context. As I started putting together the story I struggled for flow because of the lack of variety. Going from wide establishing shot, to another wide, to wide again was jarring. There was no depth to the visuals or the story. I saw clearly how different types of shots serve a story, how you can drive action, tug on emotions, and give a payoff with each one—because I was looking for those things and couldn’t find them. Their absence was glaring.

I turned to my photo archive and saw the same trend. Most of my photos are wide landscapes. I rarely think to grab a small detail or texture to compliment the grand scenes, which in a way makes sense when you’re going out to shoot single photos. If I’m thinking about my portfolio I’m looking for that one epic standalone shot, but if I think in terms of a project or series then I’m stuck with a bunch of context and nothing fill in the gaps. It took trying a new visual medium to illuminate this gap in my approach.

So what to do about it?

I knew I wouldn’t get enough reps if I simply tried to remember to shoot more tight and medium shots when I’m out. I needed more structure to make it easier to practice consistently, a project where the sole purpose was to develop my eye in this way. And so began the Dakota Series, a seven month project that took me for a ride I didn’t expect.

The Dakota Series: Introduction

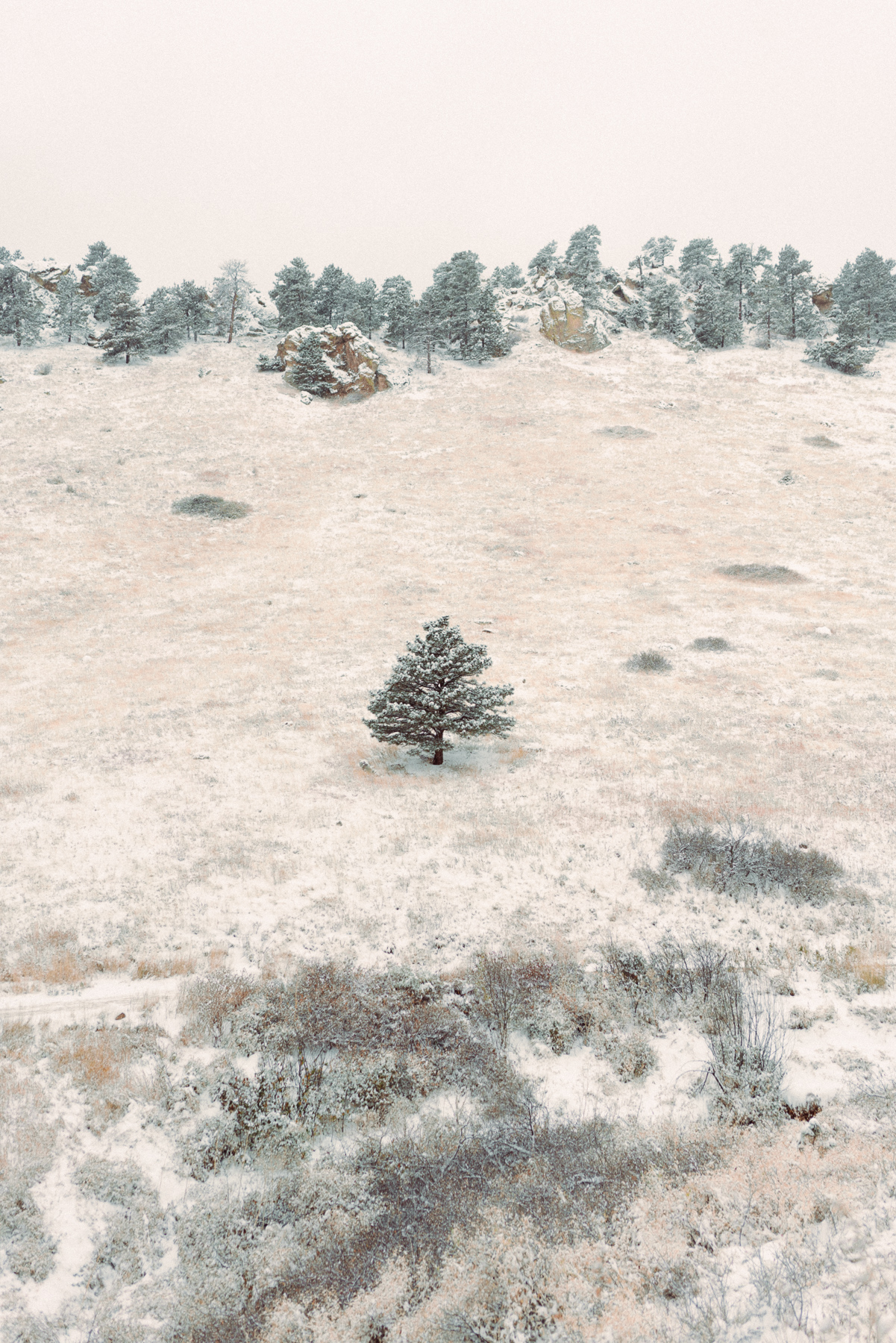

There’s a trail near my old apartment I used to take Scout on multiple times a week called Dakota Ridge. It’s easily accessible and Scout could go off leash, making it the perfect place for a relaxed photo walk. The trail sits on a hillside facing Mt. Sanitas, with a long open meadow cutting through the center. There are locals trails on either side of the ridge too offering different perspectives and a view into town. I decided I would bring my camera every time I took Scout up to Dakota, and let those walks be my time to practice.

As another constraint, I’d use the same setup for each walk. My Sony A7r3 with Zuiko 35mm prime lens. The lens is tiny, making it easy to say yes to carrying the camera every time I go out. I’ve resisted constraints on my work in the past, but found through Dakota the value it gives your process. We’re consumed by decisions all day long. Decisions drain the creativity out of our eyes. So by taking away decisions—what camera, what lens, where do I go shoot—I’m focused purely on what I’m seeing. I found the freedom many artists talk about when introducing constraints. I just had to find out for myself to believe them.

The first few walks were tame. I shot a lot of wider images still, and frankly struggled to find small scenes I felt were worthwhile. Shooting at 35mm focal length didn’t help, since it lends itself to more open views. I found myself looking down and assuming all the details worth finding would be nicely organized textures on the side of the trail. This didn’t play out well.

I shot a bunch of meh.

Then, the seasons changed. I hit Dakota at a few different times of day. My mind started doing what it does with time and space—overthinking. In this case it was for the better for once, not because I started taking beautiful small scene images, but because I started noticing trends in my photos and thinking deeper about what I was experiencing on trail. I found a different angle than my initial wide/medium/tight shot type focus.

Finding the characters of my story

I won’t bury the lede any further: I continued to struggle to shoot the smaller scenes throughout this project, at least in the way I thought I would when I started. I was imagining these beautiful, intricate scenes of plants and tree and shapes. Deft uses of shadow and texture. That was not the case.

This project has, however, taught me a lot about storytelling in my images. I hate the overuse of the word storytelling these days. It’s often thrown around as a buzzword without meaning by influencers or marketers whose “story” consists of nothing more than vibes and cinematic color grading. But in this case, story structure kept popping up in my mind and influenced what I looked for on trail.

As I struggled walk after walk to find something compelling in what I was shooting, one simple question came to mind.

Who is the character of my story?

Every story needs one. Someone or something to follow, to carry you through the events that occur. I mulled over some options:

- Dakota Ridge trail—The obvious choice I started with. Documenting the trail itself, the details of different sections, the flora and fauna, the path it carved.

- Time—The changing of seasons along the trail would provide clear changes in scenery and progression through each image. This and the trail itself easily worked together as a simple story.

- Me—Was I the subject? My journey and vision as a photographer? Did that make sense, and if I wasn’t taking self-portraits how would I portray this?

- Scout—My go to favorite subject. Always photogenic, always willing. I know how to shoot Scout well.

The trail itself was a tougher character than I initially thought it would be. I was leaning back on my old habits, shots of the trail as a leading line, different perspectives with the trail in it, mostly wide. Time was an easy fallback. I’d shoot the same images during different times of day and seasons. But that in itself wasn’t making the project interesting, and most of these shots were still wide.

I worked myself and Scout into more images, which led to better shots. Clear characters, our experience on trail. My character was more subtle, shown in shadow and POV shots, which I enjoyed. But this is also what I’m good at, shooting Scout and I’s perspective. My goal was to stretch myself and change how I see and shoot, not lean on old habits.

Then, after a handful of days out, I noticed new characters starting to pop up. Some would catch my eye quickly but fade away, like the power lines at the top of the trail. I got excited about the creative ways I could shoot them, but lost interest quickly.

But another subject stuck, worked itself into my process, and became integral to the project. A smokestack.

The smokestack

There’s an active construction site next to the trail with a white smokestack looming over it. Some research told me it was an old sanitorium before it was a hospital, now being turned into a senior living facility. The smoke stack hasn’t been used in decades, but for some reason was kept around, framing the flatirons in the background and the town below it.

I started with straightforward shots using the road as a leading line, then worked the construction fence into the foreground. As I progressed, I started noticing the smokestack popping into view from different vantage points on the trail, a touchstone appearing in different ways.

Since I was stuck at 35mm focal length and was focused on staying on the trail, the shots aren’t the medium/close shots I originally set out to find. But I was paying attention to how I was drawn to the smokestack and how my approach changed when I started looking for it from new angles, different times of day, seasons, and weather patterns. This interested me. You can see in the photos below how I was trying to work the subject over time, gathering a collection of shots that fit together as a whole.

The value of repetition

I shot around 500 images during this series. That may seem low over seven months, I’m not sure what I think about it to be honest. I never went out just blasting away, my goal was always to be intentional with what I chose to shoot.

Motifs and small characters continued to show themselves and I realized I was shooting the trail in different ways, even if still leaning towards wide shot types. Scrolling through Lightroom you can see the search happening day by day. Some days I was looking at trees, another I was in a sub-framing mood, many times I fell back on trail compositions or Scout photos, and sometimes they all sucked and you can tell I wasn’t feeling it at all.

The more I hiked the trail, the deeper I was able to look. Once I had shots in the bank it was like I checked off the list of obvious compositions and could move on to digging for more obscure opportunities. It took several days on trail before I loosened up. Then the more creative composition techniques and differing subject matter started finding its way into frame. Depth happened over time. If I had limited myself to three days on trail I wouldn’t have as complete of a set of the smokestack. Ideas would be less thought out. Time allowed all that to happen.

For projects to go beyond the surface level, I learned firsthand the value of patience and repetition. You have to have the space to explore ideas and figure out what they mean. It’s the same with writing these newsletters, the final product is often different than what I set out to write.

Editing for story

In post-production I’ve spent a lot of time trying different edits and comparing the results. I found through my edit I could create a different moment than the RAW file showed me at first. On a summer landscape I could pump up the warm tones to create a dreamy feel and to create contrast from comparative winter shots. I’d use black and white to narrow focus or shift where your eyes would normally land. Vintage colors used on an image with Scout brought nostalgia into play.

These weren’t necessarily new revelations, I’ve used edits to shift perception on photos for years. But seeing it in action within a single body of work gave editing a new purpose. It opened up shots I may not have used otherwise.

Takeaways and learnings from seven months on Dakota Ridge

Here’s what I’d have you take away from this for your own photography practice:

- Go out and do a project like this yourself. Reading this will only get you so far. Choose one camera, one lens, one place, and go shoot it over and over again. You will feel the shift over time. That feeling can’t be replicated by just thinking about it and looking at my photos.

- Embrace constraint. I always had a nagging feeling in my head when I’d consider bringing a prime lens, “But what if there’s an epic compressed shot I miss?” Get over it. Constraints free you up to focus on whats in front of you, not whats in your hand. Deploy it strategically, for specific projects as a part of the approach or to achieve a certain goal. Then you’ll get the best benefit from it. I ended up embracing this for Ultra too.

- Depth comes from time and repetition (for narrative projects at least). With Instagram offering immediate dopamine its harder nowadays to stay patient and withhold work. We want to take a good photo and share it and get the payoff. We all know the problems with this. Again, experiencing that repetition and depth for yourself is the best way to get your ah-hah moment. If you don’t have a long-term project going, give yourself a fake one like this just for the sake of practice, you’ll reap the benefits in your other work. Repetition also applies to location, visiting the same place repeatedly is what allows your eyes to cut beneath the surface. Familiarity is a friend to unique shots, a concept I didn’t believe before this.

- I’m still not good at the medium and tight shots. This part of the project I’d probably call a failure. I don’t feel like I have a new mental framework or approach for this to apply going forwards, other than to try and get closer with a wider lens. More work to be done here. If you have any tips let me know.

- Choose your character. *Super smash bros voice* Thinking through story literally is a good practice to force yourself into some semblance of structure. Who or what is my character? What is the progression I will capture? What draws me to this subject and how do I capture that? I found this process really fun during the Dakota series.

- Review the whole body of work. Many trends in my images during this project weren’t found until I was at my computer looking through them. Scrolling through a few hundred images revealed the same subjects, a compositional style, or an opportunity to pursue my next time out. I was blind to it until that point. Take the time to comb through a collection of work multiple times, you’ll be surprised what you find.

It’s obvious I found this project valuable, even though I don’t think I came away from it with any portfolio-worthy images or a deliverable. Feeling my vision change over time, watching and reviewing the progression, thinking through character and story in more depth, all help build a new approach in my photographic practice. Now I just need to keep it up, because like any muscle it’ll atrophy if not used. They call it a photographic practice for a reason.

I want to say again for effect: Try this for yourself. I hope this walkthrough gave you some tips on approach and inspiration, but the only way to feel the improvement in your work is to get out there and do it.

If you end up trying something like this, keep me in the loop with how its going. I’d be curious to see how your experience differs from mine.

Thanks for reading. I’ll see y’all again soon with more work to share.

—Al